“For everything there is a season, and a season for every matter under heaven. A time to be born, and a time to die. A time to plant, and a time to pluck up what has been planted. A time to kill, and a time to heal. A time to pull down, and a time to build up. A time to weep, and a time to laugh. A time to lament, and a time to dance. A time to throw stones, and a time to gather stones together. A time to embrace, and a time to abstain from embracing. A time to seek, and a time to lose. A time to keep, and a time to cast away. A time to rend, and a time to sew. A time to be silent, and a time to speak. A time to love, and a time to hate. A time of war, and a time of peace.”

—Ecclesiastes 3:1-8—

✦✦✦

My last public fistfight was ten years ago in a Braums parking lot in Denton, Texas.

I was 22.

It was around 9:30 at night, and I was there with a girl from one of my classes who I’d been wanting to ask out for awhile. We’ll call her Sofia. Anyway, Sofia had said yes, and after looking forward to our date all week, I’d picked her up and a few moments later there we were at the ice cream place choosing our flavors at the display. The conversation between us was light and we were having fun, until we both noticed (at around the same time) a much older man in his mid-to-late 60s leering at us from his table. Except not really at us. At her.

I don’t think she or I would have caught it, were it not for the fact that he was the only other person in the room besides the two exhausted employees behind the counter. Still, we ignored him and sat at a table at the opposite side facing away, and began eating when a few minutes later a deep raspy voice hollered, “Why dontcha come sit with me!” I saw Sofia’s body stiffen, with a fear flashing across her face resembling a rabbit caught in a trap, and which no man should ever forgive himself for causing.

“Do you wanna leave?” I whispered. “I’m fine,” she said. We started eating faster when, again, the guy shouted “Like that cream on your chin!” At which point I—being fresh out of the Army, immature, hotheaded, mistaking aggression for courage, and overestimating my abilities—stood from my seat (with my date pulling at my arm to sit back down), walked over to his table, and leaned about three inches from his face: “You’re gonna shut your mouth, you’re gonna put down your ice cream, you’re gonna stand up, and you’re gonna leave.”

This didn’t come out at all as “Liam Neeson in Taken” as it sounds in writing. My voice was shaking. My pointed finger was shaking. Both legs were shaking. Adrenaline, if nothing else, was making me look like an absolute fool made of jello. But to my surprise the man did stand up, he did throw away his ice cream, and he did walk out.

Returning to my chair, Sofia said thanks (though it was obvious she was embarrassed) and in five minutes we’d begun to relax and talk as if the situation had never happened. We thought that was the end of it. It wasn’t.

Upon walking out around fifteen minutes later, we saw this individual waiting by his car, and when he yelled something really vile at Sofia while tugging at the crotch of his pants, I snapped. Against her cries of “No! Don’t! Stop!” I ran over and threw my fist into the side of his head. What followed could be described as “a fight”… I guess, but it was more accurately a period of intense spin-hugging with occasional jabs at ribs and kidneys (and he was getting in more than me), until one of the employees came out and told us if we didn’t leave they’d call the cops. At that point the old man and I both got the hell outta Dodge and Sofia—rightfully, deservedly—never gave me a second date.

In hindsight, I shudder to think how the night could have gone differently. The man could have had a knife. He could have had a gun. It could have been my last night. Worse, my punk temper could have made it my date’s last night. I could have gone to jail. But in the heat of that moment, after I had dropped Sofia off at her dorm, the only question I had on my mind was “Why?” What aspect of a much older man’s psychology made him want to shout disgusting comments to a stranger who was easily young enough to be his granddaughter? Moreover, what could be so wrong with somebody that they are not concerned or deterred by the fact that there are other people around watching?

Most who read this account might believe that the only thing wrong about this scenario was the harassment. But you know what? No. It was more than that.

The man at the Braums was not only wrong because he said disgusting things to a stranger. If the man had been in his twenties, yes his harassment still would have been gross and shameful, but his disrespect would have been all there was to it. Yet in this case, the man’s obvious old age added an extra layer of wrongness. Why? Because his desires were not in accordance with his years. That is, one’s age should be paired with a certain set of demeanors and behaviors different from the demeanors and behaviors paired with other ages. It is not for a man in his sixties to want a woman in her twenties. If anything, it was for that man in his sixties to look at two young people on a date and feel a paternal grandfatherly affection and care for their wellbeing. Everybody has specific roles to fill. Everybody has their part to play. Everybody, in essence, has their place. And if a person insists on acting out the roles or parts of others—if they do not know their place—this is not merely an inconvenience to surrounding people or an ugly spectacle. It is disordered.

I’ll come back to that word “disordered” in a bit, and why it is that order matters so much, but right now I want to direct your attention to Quentin Matsys’ 1513 painting The Ugly Duchess:

The impulse is to go immediately to the face. Pock marked. Wrinkled. Large protruding ears. Saggy neck. The forehead and upper lip elongated. But take your attention off of the face and that’s when the painting gets interesting. The hat she wears, her garments, the red flower in her hand; all of these are intended to be signals of a young virgin woman eligible for marriage (which, in the 16th century Habsburg Netherlands, meant a woman between the ages of 17 to 21). Based on the 1511 satire by Erasmus, In Praise Of Folly, which in part makes fun of aging noblewomen “still playing the coquette” at balls and kings’ courts, Matsys’ meaning is then very plain: the duchess is deluded. She is ridiculous. Matsys was fond of inserting moral lessons into his work: the condemnation of greed in The Money Changer & His Wife (1514), the importance of resisting evil in The Temptation Of St. Anthony (1524)… and the moral of this one? The ridicule of people who didn’t dress or act their age. By attempting to stave off the appearance of age, they not only miss out on the unique privileges of being an older person (others looking to them for wisdom and advice, for example), but ironically they also make their separation from youth more obvious the harder they try to hold onto it. What is ugly about the ugly duchess is not her face, it’s her lack of grace. Her refusal to accept the inevitable.

510 years later, the more things change the more they stay the same.

Very little of modern marketing centers around phases of life. The only marketing that does do this, off the top of my head, are retirement planning brochures where old couples run along beaches holding hands because they had the right financial advisor. Other than that, clothing brands, entertainment studios, hit songs, billboards, commercials, modeling, magazines, and social media tend to portray life as an endless decadent summer which all can expect to partake in as an infinite resource and always in the exact same way. In fact to proclaim that life is divided into phases is rude. “Age is just a number.” But it’s not just a number. It’s entropy. You’re dying. You’re on your way to death. And as you get closer, your expectation and desire should be to grow in wisdom and in virtue. It is nonsensical to pretend like you’re a perpetual resident of the early stage of your death journey, when in fact you are nearing the mid or late stage.

But an essay on the phases of life would be a waste of time if we don’t know what most of them are. Nor would we benefit much without recognizing there are two kinds of phases that run in tandem with each other.

Literal phases of life:

Birth/infancy/toddler: Learning how to walk, what objects are, who people are, remembering to say “please” and “thank you”; learning to use utensils and potties and how to dress yourself; keeping food in your mouth; drawing on paper not on furniture; coping with the disappointing truth when your dad tells you Mickey Mouse isn’t real. Thing you long for most: Being one of the big kids.

Childhood: Learning how to swim and ride a bike; when to stand up for yourself; that sometimes you have to do things you don’t want to do (eating vegetables, homework, chores, cleaning your room, etc.) Thing you long for most: Fun.

Teenager: For most, a time of first love and first heartbreak; recognizing your parents aren’t perfect; finding out that not all “friends” are friends; learning to drive; working a first job. Thing you long for most: Freedom.

Adult/20s: A time of exploration, where you go off to college, trade school, the military, perhaps even travel abroad; a time of parties, of adventures and misadventures, of taking on philosophical and political ideas; figuring out how your personality helps or hurts you, and what skills and talent you need to cultivate in order to survive in the world. Thing you long for most: Belonging.

Adult/30s-40s: Typically the marriage and kids window; balancing fun with responsibilities; maintaining (struggling to maintain) good finances and budgets; taking calculated investment risks; coming to grips with your body’s early signs of decline (hair loss, pot belly, first wrinkles, skin sag, etc.); a predilection for avoiding the radical and “avant-garde” music, movies, books, and ideas you were once drawn to, in favor of the conventional and the safe (at 24 you cheered with your friends watching Fight Club, at 44 you cry with your daughter watching Paddington 2). Thing you long for most: Stability.

Adult/50s-60s: A time of “empty nests” and worrying about your newly-grown kids going out into the world; figuring out with your spouse what marriage looks like with just the two of you again; taking up new hobbies or resuming old ones; more traveling, vacations, roadtrips; perhaps reconnecting with old friends with whom you previously lost touch. Thing you long for most: Legacy.

Adult/70+: Everything hurts, pain is constant; you are retired or at least working less; every family member has their own life apart from you; the batch of humans you began your life with have almost completely been replaced by humans you’ve brought into the world or have seen brought into the world; the ground has shifted beneath your firmly-planted feet technologically and culturally. Thing you long for feel the most: Contentment, resignation, both?

These literal phases don’t matter so much themselves as they do when paired with the emotional phases of life:

Understanding that whining and tantrums are not a way to get what you want. No longer fearing the dark. Gradually seeing shadows on the wall, trees outside windows, and piles of clothes under the bed as being what they are and not as monsters. Learning that scrapes and bruises and spilled milk are unworthy of tears. That the love of a mother is different from the love of a father, though they are equal in measure (this is intuited more than consciously learned).

Being a good sport in losses as well as wins. Figuring out that there will always be bullies, and the only “zero tolerance” that works is your zero tolerance of being their victim.

Admitting to yourself that you are quite capable of becoming highly attracted to the physical beauty and personality of another person (albeit, in most cases as a teenager, for only a few weeks or months). Discovering the importance of developing and setting personal boundaries, and recognizing and respecting the boundaries others have set.

Dealing with the conflicted, happy, sad, or confused feelings that come with the loss of virginity. Discerning what qualities you want or need in a spouse, and doing the necessary self-inventory and work to become worthy of that kind of spouse. Coming to the recognition that just as you are the main character in your mind, so everyone else is the main character in theirs, and that this enormously complicates the defeat of the ego.

Feeling (with some urgency) the importance of giving your kids a good childhood, and shielding them from grown-up worries and troubles behind the scenes, just as your parents (hopefully) shielded your childhood from their worries and troubles. Looking for ways to maintain intimacy and connection with the spouse you’ve been married to for ‘x’ amount of years, and “keeping new” your old love.

Grieving the death of your parents and learning to feel at peace in a world without them. Recognizing that some doors in life are now permanently closed, and it does not do you good to dwell on those doors, but to focus on ones still open.

Grappling with the emotional weight of most of life having passed. You no longer think in terms of dreams or goals to achieve, but rather take inventory of decisions made and risks not taken. If you’re religious, you spend more time thinking about the afterlife than you ever have before. And as you watch your grandkids grow, you come to accept that your being lowered into the ground will not weigh the world down enough to slow its spin. Not for one second.

Let me be clear: I am not about to make some stupid suggestion that you can’t skip or “be late” for one or more of these, or that the literal phases have remained consistent across centuries or even decades. Indeed a few of these, due to circumstances beyond anyone’s control, won’t apply to some.

No, the problem is that our society has a penchant for pretending that—when it comes to psychological and moral growth—these phases don’t exist as meaningful markers at all. Our obsession with choices and the ability to choose is entwined with a conviction that there are no unwise or false choices, no longterm consequences that can’t be avoided, nothing besides the warm relativistic waters we bathe in that we are convinced will never get cold. “That’s great for you but not for me”-ism.

You’ll notice that most of the life phases above hinge on parents and children. How many times did they come up? I won’t count, but it was a lot. And the phases I mentioned that didn’t involve parents or kids mostly touched on romantic love in some way. That’s because becoming the kind of person that helps to build and preserve civilizations and generations involves the complete giving and sacrifice of oneself to relationships that transcend (and often transgress against) personal pleasure and comfort. Our ability to discern our purpose is contingent upon our ability to look at others forward and back in time to consider why (because there is a why) we have been created to live in this particular time and not in a different one. Another way of saying this is that the act of living out certain milestones is to consider what is, at root, a protological question: “What were we born to do, when are we supposed to do it, and how—as far as immaturity—are we to remove what stands in our way?” The years, like river currents, should gradually pull each of us away from our loud, surface-level, unattached selves toward becoming contemplative, mystical, and rooted.

And this is why I’m bothered.

The first sign of a society that doesn’t want to accept phases of life—a society that is, in essence, terrified of giving up its youth—is that people no longer make marriage a goal. Marriage is just a thing that “happens” if it happens at all. People no longer make children a goal. Children just “happen” if they happen at all. To treat marriage and children as anything other than incidental occurrences along the pathway to “real goals” like a career or education, is to invite a very long talking-to from a concerned parent, friend, or coworker fully catechized by secular capitalist liberal culture.

I should note more clearly that this is not a judgement of individuals. Certain men and women may—after a lot of time and reflection—wisely determine they would not be good or patient parents and spouses. It is not always selfishness or materialism or shallowness that causes people to want to live their lives alone. But while a conservative should never sit in judgement of individuals on these matters, when an entire culture collectively rejects marriage and parenthood as states we should naturally progress toward by default, it’s hard not to see this as a symptom of us Not Ever Wanting To Grow Old.

But without even touching the deeper subject of our reluctance to embrace matrimony or parenthood, one could easily spot exterior markers of a people who do not want to give up their youth:

Middle aged men wearing “hip” clothing they do not belong in, and going to clubs to attempt to pick up girls they’re old enough to be the fathers of.

Middle aged women trying to be popular with their teenage daughters and daughters’ high school friends, by allowing them to do things within the confines of their home no parent should be fine with their child doing.

60-year-old men talking about sex like they’re still 14. Women in their 50s at bars dressed in leopard print.

An estimated 287,000 Americans underwent facial plastic surgery last year alone. That’s not counting how many underwent balding treatments, botox treatments, liposuction, or tried to make their breasts, butts, or dicks bigger.

Kurt Andersen, the novelist and cofounder of Spy Magazine, noticed the same trend among adults when he remarked in 2018 at the Saturday Evening Post:

“Americans have begun saying and wishfully believing about round-numbered ages that ‘X’ is the new ‘Y’… 30 the new 20, 40 the new 30, 50 the new 40, and so on. Yet in so many ways they’ve all become the new 15.”

But understand: This non-acceptance of aging and adulthood—and refusal to draw a clear distinction between mid-life and youth—can only lead to embarrassing and tragic outcomes.

To elaborate on how, it’s time for me to bring out that word “disordered” again and explain it.

Deriving from the Latin Ordo, order was envisioned by the Romans and later medieval scholastics as that which was characterized by “a row, a line, a rank, a pattern, an arrangement, a routine”; almost certainly imagery built upon the earlier Ancient Greek philosopher Plato’s “theory of the forms”, wherein a realm outside of the physical exists where concepts/ideals (forms) of things reside that are more real than things themselves in the physical realm, which are mere imitations of their concepts/ideals (forms). As beings who are not just physical but spiritual, our minds are “tapped in” to this realm of perfect things by which we judge the things of our own. We know that a good house must have walls and a roof because in the Realm of the Forms, there exists a perfect house that has walls and a roof that informs our judgement of what a functional house is. The Judeo-Christian version of the Realm of the Forms is only slightly altered: God—who is Perfect Being Itself—in the act of creating, could only create perfectly. But in our Fall we detached ourselves from the “ought be” yet not the memory (itself an echo of a restoration to come). The Realm of Forms, then, is not an outward place, but an inner voice that is not our own. Yet whether one takes the Judeo-Christian version or not, the Platonic theory is essentially the same: we have an objective concept of items by which we judge the items we see in real life. These objective concepts are innate and can only be removed by determined and sustained acts of willful ignorance.

Take, for another example, a ball. A ball is round. The less round a ball is, the less it is a ball at all. And the less it is a ball, the less useful it is period. A “non ball-shaped ball” cannot serve some other function. A flat ball can’t be a table or a cabinet or an instrument. Moreover, you cannot change the reality of a thing by changing what it is called. Language does not form reality, reality exists independently of language. If I refer to the non-ball as a “table”, it still is not—nor will ever be—that piece of furniture we eat on called the same.

In short, to believe in order is to believe there is a general intention that “makes up” and “informs” every single object and person in the universe, and the farther away from that intention something drifts, the more it becomes what it was not meant to be. The more it becomes disordered.

A harsh truth that our society is not receptive to hearing is that the same ordo or “form” that applies to a ball applies to age. An old man or woman must act with the wisdom the “form” of their age calls for, and if they do not, they will be useless. If an old man or woman refuses to act with the wisdom the “form” of their age calls for, they cannot simply function as different kinds of humans (though they’ve convinced themselves they can). They cannot function as teenagers. They cannot function as a guy or girl in their early-20s. And the more they try, the more disordered they appear, always coming across as less than what they’re supposed to be and simultaneously never seen as how they wish to be seen. Which makes them not only inwardly anguished but outwardly off-putting.

With that definition of order and disorder in mind and how it relates to the person, we can scale up: What does an ordered society look like? And why should we want it?

An ordered society contains people in a constant state of growth embracing the tasks, appearances, and attitudes expected of their years. As such, these are people who understand consequences, trade-offs, delayed gratification, and doing without. These are not people who are lured by baby talk, or soundbites, or bumper sticker slogans on important issues. They are not taken in by easy-to-see scams, or prone to believing they can achieve success quickly, or addicted to drama and gossip. And we should want that kind of society because that kind of society—the optimal society—passes down values no other lesser society can: patience, restraint, thrift, moderation, courage, resolve, tenacity, mercy, honesty, goodwill, respect.

To shirk our duty to become this sort of society is cowardice. As the early-20th century Christian philosopher and critic G.K. Chesterton once wrote:

“Most modern freedom is fear. It is not that we are too bold to endure rules but too timid to endure responsibilities.”

And yet one cruel aspect of this crisis of our time is that even if one wants to grow up, many of us no longer know how. For men, the questions that precipitate a yearning to become more than what they currently are might be as follows: “What happens when the musical genres I enjoyed in my teens and twenties now start to sound like noise?”, “What happens when I no longer have the vigor and stamina to play sports as well as the younger men and it shows to the people watching?”, “How do I think about my self-worth when I begin to earn less than I used to earn or am ‘aged out’ of business leadership positions altogether?” For women, the questions could be very similar: “What happens when the pop songs are no longer about things that are relevant to my life?”, “What happens when the lead actresses in movies meant to be ‘the catch’ look like children to me?”, “What will the impact be on my life when I start losing my looks?” And even for those men and women who have made some sort of peace with the passage of time in a way their peers have not, there still might be the nagging question: “How do I mature into my age emotionally without becoming a total stick in the mud? How do I maintain a good sense of humor and show a love to others that is full and radiant, while behaviors that have long ‘been me’ are deliberately discarded?”

These questions and similar ones are met with crickets by a culture that doesn’t provide a path for people to age gracefully, because a culture afraid of giving up youth worships youth.

At a glance, youth worship may seem like a sign of vitality and progress and fun, but in fact the opposite is true. Youth worship takes place in cultures of death. It confines its elderly to “care homes” out of sight of the general populace, treats its middle aged like ATMs, doesn’t like unruly babies killing its vibe, and only has an appetite for the demographic most susceptible to the appeal of buying things: 15-30; thereby incentivizing anybody outside of that range to try and be as much like it as possible. Cultures of Death, in other words, built on twin foundations of secularism and consumerism—though obsessed with youth—eventually become starved of young people. (Who would have thought? The more a country doesn’t make children, the less future customers it has to advertise to.) By contrast, cultures with foundations in more ancient value systems than liberal capitalism—religion, ancestry, military hierarchy—are far more likely to be cultures that honor their elders, have adults who are relatively comfortable being adults, and also tend to have more young people. In Israel for example, where the old are not frequently confined to “care homes” and the middle aged comprise a significant portion of film and music artists, there are babies and toddlers everywhere. Teenagers and university students hold hands and kiss everywhere. More importantly, 50% of Israelis under 25 are married compared to 23% of Americans the same age (despite identical levels of economic inequality in both countries), while the Israeli divorce rate is 24% below the American national average. In the historical sense, Israel and the Jewish people are one of the oldest civilizations in the world and America the youngest. But in the societal sense, the inverse is the case. Israel is a “young old” country and America is an “old young” country.

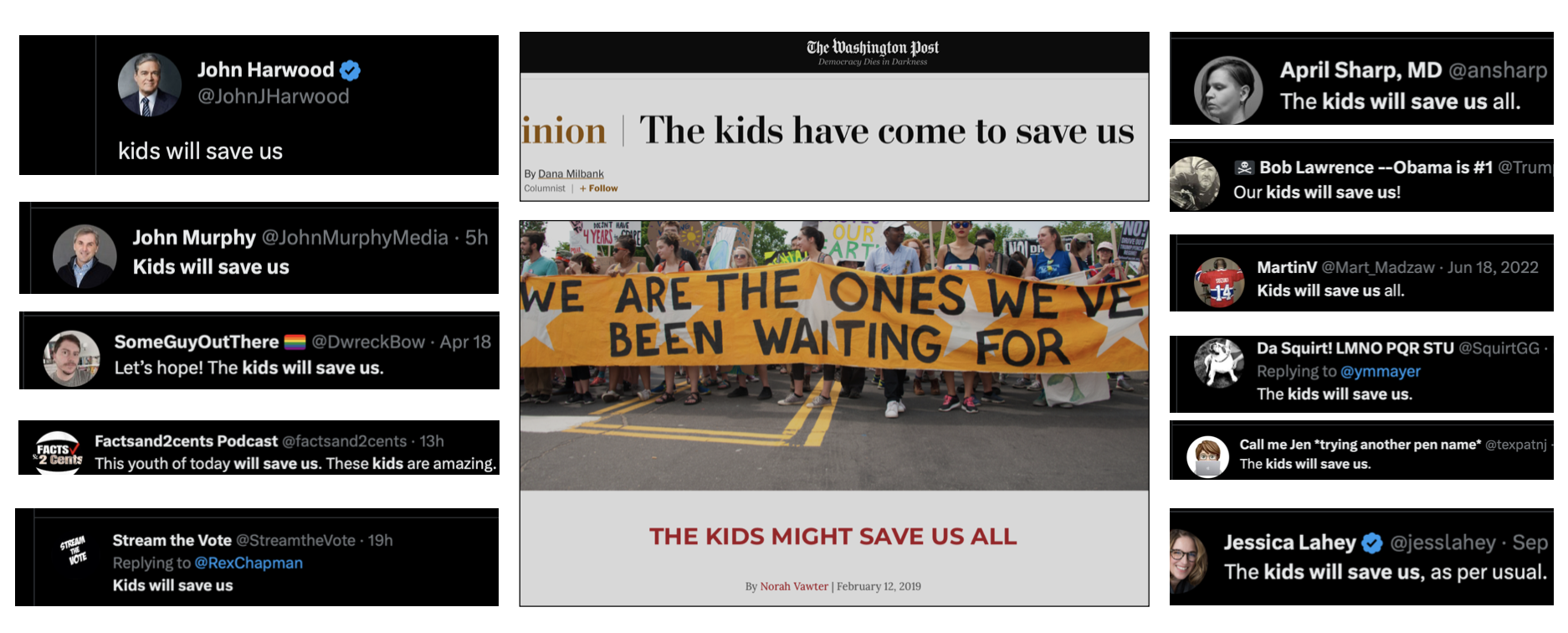

But a secondary way Cultures of Death worship youth, after its primary way that centers around the consumption of goods, is the self-centered statement expressed by its citizenry that—when it comes to economic, environmental, foreign policy, or social crises—“the kids will save us”. Self-centered because so often it is voiced by those citizens who did not have kids at all, nor liked being around them, nor looked kindly on those who had more than two, nor seem to think one “kid” might be different from another in terms of capability. We could say that “The kids will save us” is a statement of faith, but actually it’s worse. It’s a statement of desperate and undeserved hope. The confession of a generation that “We were too apathetic or disheartened to do anything about anything that mattered, so we’re hoping ‘the kids’ [other people’s] will come along and clean the messes.” To say the “The kids will save us” is to admit being a burden. A drag. Dead weight.

And though you may be among the few fortunate to have not heard “The kids will save us” in the last ten years, you certainly have encountered its even dopier, dumber, emptier cousin in schools and public libraries: “Children are the future.”

No shit they’re the future, thanks for telling us how time works.

Yes “children are the future” but that doesn’t actually mean anything.

Certainly it doesn’t mean that because they are the future—because they possess more potential years than older people by virtue of their birth order—they somehow have this innate ability to solve complex problems right now (an ability that… I dunno… is supposed to somehow dissipate once they hit your age, so they can make way for the next batch of “kids” who will “save” them?) It used to be commonly understood that teenagers and young adults, during their time as teenagers and young adults, were not at the pinnacles of their knowledge. With their age came a tendency to be extreme, prideful, impulsive, “invincible”, and unappreciative of complexity and nuance; and only with additional years of experience (“hard knocks”) and wise counsel from their elders would those tendencies start to change. This is because young people, generally speaking, when starting out in the world, don’t have an adequate grasp of enough reality to fix reality. The fact that this traditional view of the young (backed up by plenty of first-hand experience by plenty of generations across cultures) is now in question, reveals how the worship of youth has spread through our Cultures of Death like cancer.

Take this gem, for example, from AnneMarie Hayek’s 2021 book Generation We: The Power & Promise Of Gen Z:

“To dismiss Gen Z as the latest teenage Pollyannas, sitting in circles wistfully singing ‘Imagine’ fails to recognize that they possess tools no other generation has had. Technology has linked them since early in their lives, and they’re the first generation to truly harness the power of social media. That gives Generation We [Z] unprecedented potential to revolutionize almost every aspect of life and society.”

“Yes yes you stupid man, I know that maybe previous generations didn’t get it right when they were young, but this latest one won’t fall victim to naivety because they have ‘tools’. This latest one won’t need to worry about discernment, benevolence, humility, or self-control because they have social media. Technology confers wisdom, dontcha know.”

But if Generation We turns out to be the most obnoxious book published in the 2020s, Hayek’s Amazon reviewers won’t know it.

Writes one: “This new generation is so far ahead of us and has so much power to make things move!”

Who is “us”? What does “so far ahead” mean? “Make things move”?

Another writes: “The smart, passionate, fair-minded youth of today look at the world and know exactly what to do to fix it.”

Yeah, sure, they know exactly what to do. At 19-years-old. They know exactly what to do about global and national problems when they don’t even know themselves.

Yet when large portions of a population in a Culture of Death refuse to be people of any kind of substance whatsoever—instead pursuing unhindered consumption, eating, and sex—there is no other option than for them to hope for outside salvation (though even the needing of salvation would elude the selfish masses, who would confuse their need of it for a need for “happiness”, and thus would likely miss the boat even if it docked directly in front of them).

Having abolished any notion of exclusive roles, responsibilities, behaviors, and privileges across categories of gender and age as “rigid”, “patriarchal”, “ageist”, and “outdated”, the only thing left is the atomized individual with nothing but whim and trend to inform the direction of their lives. And the only frame of time that can exist in such a fragile construct as that is the present. There must be no consideration of the future. There must be no connection, knowledge, or interest in the past. Ancestors, traditions, and creeds—when or if they are thought about at all—are to be thought about abstractly and rebuked, not adored and certainly not to be thought of as a foundation upon which to build one’s life.

Here my mind travels (awash in piss and vinegar) to part of Wendell Berry’s poem The Objective:

“Men and women and children now pursued the objective as if nobody ever had pursued it before. The races and the sexes now intermingled perfectly in pursuit of the objective. The once-enslaved, the once-oppressed, were now free to sell themselves to the highest bidder, and to enter the best paying prisons in pursuit of the objective… which was the destruction of all enemies. Which was the destruction of all obstacles. Which was to clear the way to victory. Which was to clear the way to promotion. To salvation. To progress. To the completed sale. To the signature on the contract. Which was to clear the way to self-realization, to self-creation, from which nobody who ever wanted to go home would ever get there now. For every remembered place had been displaced. Every love unloved. Every vow unsworn. Every word unmeant. To make way for the passage of the crowd of the individuated, the autonomous, the self-actuated, the homeless with their many eyes opened toward the objective which they did not yet perceive in the far distance, having never known where they were going, having never known where they came from.”

_____

When we consider the personality types, attitudes, and demeanors of a populace largely interested in not acting their age, one could easily point the finger at extremes like “married fat Leather Jacket Man in a brand new sports car honking at campus joggers”, or “woman with the heavily-powdered wrinkled face and whiskey breath grabbing at the crotches of strangers under neon” for being the sorts of people who provide best proof of the issue. But by focusing exclusively on the middle aged “offenders”, we come to grasp only one half of the problem of Cultures of Death afraid of giving up their youth.

The phenomenon among people in their 40s and 50s being the “eternal 21-year-old” runs parallel with a phenomenon among people in their 20s of trying to be the “eternal kid”. Younger adults who—rather than feel the need to preserve sex appeal—instead feel the need to retreat into preadolescent posture as a way of coping with a world and workplace that is often careless and chaotic. After all, if culture has become so hostile to adulthood that even adults try to escape it, and if it’s “the kids who will save us”, there’s incentive to transition from thinking of childhood as momentary to treating childhood as aspiration.

This becomes doubly potent if one becomes conditioned to associate with childhood only the positive feelings of playfulness and wonder and possibility, while being given a false impression that the only things that await the adult are debt, long working hours, loneliness, and only pleasures that are superficial and fleeting. Not meaningful friendship, not property ownership, not true love, not retirement. Or… if those nice things are possible, the odds of attaining one or all of them are so low that one is likely to just get badly hurt in the process of attempting to attain them, so why try? Better to just avoid pain by sealing oneself off as much as possible in perpetual Toyland.

The presenting of oneself in young adulthood as “still just a kid” is solely about this. The avoidance of pain. The fear of being hurt beyond recovery. Running from any and all tribulation, believing nothing to be transformative and all to be destructive.

Freddie deBoer, an author and blogger who I’ve been reading for the better half of a decade, wrote something recently related to this that I think is right on the mark:

“Basic dynamic in life: there is nothing meaningful enough to make you happy that could not make you sad if you lost it. This is the paradox of feeling, and it’s inherent and existential. If things inspire real positive emotion in you, then they are necessarily things in which you are sufficiently invested that you would feel negative emotions when they’re gone. One of the fundamental choices that you face on earth is the degree to which you’ll pursue deeper but riskier fulfillment, or practice avoidance that exempts you from bad feelings but leaves you bereft of good ones.”

I can’t count how many times I’ve seen this in acquaintances who are 24, 25, 26: “I don’t want to move out of my parents’ house because what if I can’t make rent and wind up homeless?”, “I don’t want to get married because what if I wind up divorced?”, “I don’t want to have kids because what if they grow up to be awful?” And the only answer to this kind of fear is that you can’t avoid pain without avoiding joy. To empty life of pain is to empty life of all. Sometimes becoming financially independent takes time. Sometimes you screw up along the way. Sometimes you have to budget, and re-budget, and re-budget again. And yeah, divorces happen. They do. Sometimes people who have traditional values and who are committed to their spouses nevertheless find themselves divorced. Sometimes your kids grow up not to like you. Even if that’s not your fault. Even if you showed love to your kids as best as you knew how. But you know what, for the vast majority of human beings on earth, financial independence, marriage, and parenthood are worth taking chances for. You would probably wind up regretting failed financial independence, a failed marriage, or a failed parenting relationship a lot less than you would regret never having tried those three things. The unknown is always worse than the known.

In recent years we’ve seen a barrage of literature and product rollouts that have—for those of us who once looked forward to and now fully embrace our adulthood—raised eyebrows: the construction of Disney-themed neighborhoods, this line of adult cartoon backpacks, the New York Times article titled The Case For Sleeping With Stuffed Animals As An Adult, another article by Thrillist listing the Best Kids Meals Adults Can Order At Restaurants, market research showing that the biggest driver of sales in the toy industry is adults buying toys for themselves.

And to this I can only say… fine. Be an infant your whole life. Hide in childhood forever. Never begin the Hero’s Journey. Never discover your archetype and live its story. Take no risks. Numb yourself. Stay in your room all the time with Cheetos, video games, and TikTok therapy videos. (And porn… also porn… because while most of you is involved in active denial about your true age, there’s at least one part of you that acknowledges it). And when somebody is “rude” enough to suggest you’re a loser for behaving like this, just tell them they’re making your anxiety worse and tap your shoes three times. There’s no place like home.

You think I’m mean. Okay. Yes. When it comes to this, I am mean. I never thought “nice” was a real virtue anyway, and the complete abdication of our roles really gets under my skin. Because it not only lets down previous generations who raised us and depended on us to take over for them; it abandons later generations of actual kids and teens who need wisdom, need guidance, need help, and can find nobody, because everybody 5, 10, 15, 20 years older wants to say “I’m just like you.”