“Life’s the same. I’m moving in stereo.”

—The Cars—

✦✦✦

The way I like to read the Bible is either at sunrise or sunset on the apartment balcony with a cigar and a coffee (if it’s morning), or a cigar and double stout (if it’s evening). To sit with the words of God while enjoying flavors of oak, leather, almond, chocolate, cream, and pepper is the kind of activity that lends itself to intense reflection. It’s a very addictive and calming kind of solitude, and one I think too many young men are missing out on the warmth and richness of.

Yesterday evening, after lighting a Kristoff Maduro and changing things up by pouring a glass of red wine, I opened up Ecclesiastes; the seventh of eleven books in the Ketuvim and the third book in what’s called the “wisdom literature” of the Old Testament. And though it wouldn’t be quite right to classify the book as a “memoir” of King Solomon, it is his look back on his reign and a meditation—not on what his legacy is—but rather on the futility of legacy. In a situation where most rulers would be tempted to gloat about the importance of their achievements while in power, the Israelite leader instead challenges enemies and admirers alike to think about what achievements are actually worth in the long run.

“All is vanity.”

If you listen, the words have an echo.

Like a rock tossed into a crevasse reverberating loud, then less, then no more.

ALL IS VANITY

The phrase conjures an image of everything and everyone you ever held dear being evaporated by a split-second belch of the sun—including memory and record of everything and everyone you ever held dear—so that not only do those things and people no longer exist, but they may as well have never existed at all, with no one to tell of their “onceness” in the universe.

Bleak. Unforgiving.

These three words “All is vanity” are Jewish proverb at its finest.

The edge of a sword spilling your insides with a single swing.

Or maybe “All is vanity” is not so much intended to be grim, as it is a statement of exasperated annoyance. It’s not the sun evaporating anything. No, it’s an itch you can’t scratch. A fly you can’t swat. A tapping sound whose source you cannot find. That actually seems to be what’s more in line with the tone of the author.

Paraphrasing verses 1:12 to 2:26, Solomon says “I sought fulfillment through increasing my wisdom. It didn’t work. I sought fulfillment through liquor. It didn’t work. I sought fulfillment through gardening. It didn’t work. I sought fulfillment through wealth. It didn’t work. I sought fulfillment through humor. It didn’t work. I sought fulfillment by having lots of sex in lots of different positions with lots of different women. That didn’t work either.” You catch on to his irritation as he jumps from one project to the next, feeling momentary flutters but eventually growing bored and longing for something that will last. Something enduring. Something eternal.

These writings bear a striking similarity to Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations written a thousand years later. Compare, for example, the sentiments of Solomon in Ecclesiastes chapters 1-2 with Marcus’ Meditations in Book 2, Verse 12: “How quickly all things disappear, in the universe the bodies themselves, but in time the remembrance of them; what is the nature of all sensible things, and particularly those which attract with the bait of pleasure or terrify by pain, or are noised abroad by vapory fame; how worthless, and contemptible, and sordid, and perishable, and dead they are.” Or compare Ecclesiastes 3:1-8 with Marcus’ Meditations in Book 12, Verse 21: “A little while and you will be nobody and nowhere, nor will anything which you now behold exist, nor one of those who are now alive. Nature’s law is that all things change and turn, and pass away, so that in due order different things may come to be.”

To those readers of scripture thrown off by Ecclesiastes’ cynical and even atheistic tone that feels so out of step with the rest of the Bible, looks can be deceiving. Solomon is not a nihilist. Solomon is merely presenting life on its own terms. If no God, then no permanence. If there is no Source of All outside the entropic bubble—eternal, omnipotent, immutable—then all is bound by time and space and can only go to irrevocable decay. Solomon seeks to imbue his readers with this despair, waiting all the way till the final chapter to reveal that only with service to others and friendship to God do the “vain” and “transitory” things have significance. Work for its own sake is a waste. Sex for its own sake is a waste. Laughter for its own sake is a waste. Wine, gardening, and wisdom for their own sakes are wastes. But when these things are done in divine communion, suddenly we recognize that what is good in all of those things will be perfected in the life to come. That whatever small and temporary joy we experience in the fallen cosmos will be magnified and made infinite in the New Heaven and New Earth.

This short 12-chapter treatise is a jewel among many in the crown of scripture. Beliefs about religion and inspiration aside, it would take a very foolish person to deny that the Bible was the greatest literary achievement of mankind for at least 2,000 years until—perhaps—being matched (not exceeded) by the plays of Shakespeare. In terms of the Bible’s chronicling of human depth, suffering, promise, tragedy, joy, triumph, and yearning, you simply don’t find “grand sagas” being written that are as ambitious until well into the 20th century.

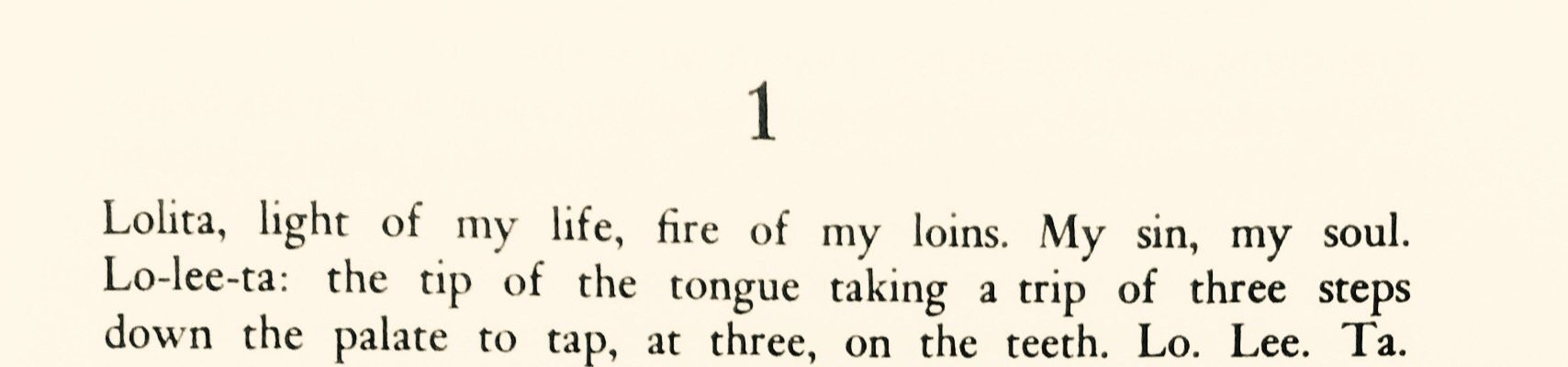

In fact, for a brief digression, one theory I have about Russian novelist Vladimir Nabokov is that in the opening paragraph of Lolita, he adopts a rhythm based on the rhythm of Solomon’s opening in Ecclesiastes 1:2.

Vanity

Of

Vanities

Light

Of

My Life

All

Is

Vanity

Lo

Lee

Ta

Nabokov—despite having an intense dislike of organized religion—frequently used biblical themes in his work, and his reason (I believe) for the parallel between Lolita and the biblical character of Solomon is the Israelite king’s pursuit of a younger woman in Song of Songs. Hence, the name Lolita serves as a warning to Nabokov’s own protagonist that the conquest of a young girl will not bring him fulfillment. Rather, just as Solomon, Humbert will come to the end of his pursuit bitterly recognizing that the satisfaction of his lust has not satisfied him. Even Humbert’s name I feel is a hint at the Solomon inspiration; as Nabokov, when asked how he came up with Humbert, said “It sounded kingly.”

But back to Ecclesiastes and back to the main point: lately I’ve gotten into the habit of hearing music while reading, and this evening as I read Ecclesiastes, my 70s/80s playlist queued up The Cars.

Combining the Bible with classic rock can have its pitfalls. You don’t want to read about David and Bathsheba against Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “What’s Your Name”. Nor would Foreigner’s “Waiting For A Girl Like You” be a good fit for Hosea. But if you’ve ever watched the movie Kingsman and seen that awesome gunfight scene with Colin Firth set to “Freebird”, you’ll have a blast when you play that track while reading about Samson slaughtering a thousand men with a jawbone. There’s also no better song for Jacob fleeing for his life (twice) than “Renegade” by Styx.

Yet it’s the similarities between the ancient Israelite scroll and the late-70s new wave band that’s holding my attention tonight. It seems like both are singularly obsessed with the fleeting nature of life and the “vapor” of time. Ecclesiastes repeatedly emphasizes our transience, with Solomon bemoaning life “as a mist here today and gone tomorrow”, and similarly many of the songs by The Cars also touch on our ephemeral nature: “Moving In Stereo”, “Good Times Roll”, and “Drive” all shroud cryptic messaging in tranquil or upbeat melodies; as if the juxtaposition is supposed to jar any listener paying attention. The grappling of Ecclesiastes and The Cars with the fleeting nature of youth and fun against the inevitability of aging and death, if anything gives us a hint that the sentiment is timeless of “Wishing we could know when the good ol’ days were before we left them.”