“Ah,” said the Marquis of Saint-Méran, a woman with forbidding eyes, thin lips, and an aristocratic and elegant figure despite her fifty years, “If all those revolutionists who persecuted us during the Terror were here now, they would have to agree that ours was the true devotion, for we remained faithful to a crumbling monarchy while they attached themselves to the rising sun and made their fortunes while we were losing everything we owned. They would have to admit that our king was truly Louis the Beloved, while their usurper was never anything except Napoleon the Cursed. Isn’t that right, Monsieur de Villefort… the Bonapartists had neither our conviction nor our devotion?”

“Yes, madame, but they have something which replaces all that: fanaticism. Napoleon is the Mohammed of the West for those vulgar, highly ambitious people. For them he’s not only a legislator and a master, he’s a symbol. The personification of equality. While Robespierre represented the ‘lowering’ equality of bringing kings to the guillotine, Napoleon represented the ‘higher’ equality of elevating people to the throne.”

—The Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas—

✸

For those who think of the medieval period (accurately or inaccurately) as a black cloud which hung over a Europe steeped in ignorance, malice, and drudgery—only in the 18th century beginning to see the sun rise over its blackened valleys of wasted time and potential—to read about Napoleon is to read about an almost messianic figure. There’s even a brief description in Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables, where the emperor is riding his horse through the pouring rain late at night while his subordinate is desperately trying to catch up; and at the moment he finally does, he sees the soaking conqueror look toward god, stretch out his arms, and—just as the lightning cracks—shout “You and I are one!”

I am envious of this moment, fictional though it likely is.

How must it feel to catapult from second lieutenant to ruler of France in 14 years? How must it feel to go from governing a fledgling republic—in constant danger of invasion by surrounding enemy states—to conquering the continent in a decade?

In the whole span of human activity on this planet there are only a few figures who, over the course of their lifetimes, have gotten to discover firsthand that the combination of idealism, bravery, ambition, and power—real power—is seductive, intoxicating, and unfortunately often doomed. These figures dance on the pages of history like whirling beautiful flames, there to remind us of the heights mortals can reach, though we may never personally reach such a height ourselves. But these rare flames who grace the records of our past and mesmerize us also—normally—die young, or if they do not die physically, their spirits are extinguished; as if some undiscovered law of the universe demands a rebalance for the disproportion in excitement they experienced and generated.

In this essay, I’m going to subvert the typical outline structure and state my conclusion first: that Napoleon was an “Enlightenment conqueror” ruling an empire of the proletariat. His invasions of kingdoms was the major catalyst that turned Europe democratic, and this was not unintended. He knew that the old monarchies had no intention of allowing their people to acquire self-governing powers. And this is why, in nearly all cases after Napoleon conquered a country, he would either install new egalitarian governments with new constitutions or, at the very least, leave the defeated monarchies so weakened that the peasants under them had the opportunity to demand self-governance. Before Napoleon, the Enlightenment had stalled, and by the late 18th century many European countries were still ruled by royal families who showed no signs of leaving the scene. At this point, the Age of Enlightenment and the emergence of republican democracies appeared to have just been a fad. A flash in the pan. It would take the ambitious third son of an inconsequential attorney from a backwater island to change this. The Ted-Ed narrator of an animated history put it succinctly when he said:

“It was thanks to Napoleon that the continent was reshaped from a chaotic patchwork of feudal and religious territories into efficient, modern, and secular nation-states where the people held more power and rights than ever before.”¹

The fawning may sound excessive, the accomplishment oversimplified, but if there is anyone whose very existence seems to contradict a Marxist interpretation of history, it’s Napoleon. That is, if figures in history are merely swept up by economic and social tides that are beyond their control individually, and if even their actions to a great extent are puppeteered by these forces, it wouldn’t occur to anyone that a boy from Corsica would break from that norm. But even acknowledging Napoleon as an exception to the dialectical materialist “rule”, we still must look to a revolution that did set the stage for his rise.

In 1787, were you to tell King Louis XVI that in 25 years, France would conquer Egypt, Belgium, Holland, most of Italy, Austria, most of Germany, Poland, and Spain, he would look at the state of the treasury and howl. He would do this because France’s treasury had been depleted after the Seven Years War, assisting the American colonies in their struggle for independence, as well as by trying to maintain a large navy to compete with the British Empire. But then, once you convinced him that you knew what you were talking about (without revealing you were a bonafide time traveler), and that you knew that in 13 years the treasury would begin to be replenished by the spoils of war, the king would be elated. Were you to go on to tell Louis, however, that a revolt would soon end his reign and that he—age 32—would not live to see his nation reach these glorious heights, he would howl again. And why wouldn’t he? The boldest astrologer, palm reader, tea leaf interpreter, or numerologist would not dare stake their lives on such outlandish predictions.

And yet there were obvious signs that Louis ignored pointing to the turmoil that was soon to erupt. Peasants throughout the country were starving, particularly in rural areas where farmers had to take on additional seasonal labor to make ends meet. The elimination of state pensions and the sudden raising of taxes—which only commoners paid, as the nobles were tax-exempt—crippled said commoners, and worse, the revenue was still insufficient to cover the nation’s debt (facts which modern proponents of trickle-down/austerity economics seemingly fail to take note of). Furthermore, no European bank would loan France any money, because they all knew France was in such dire financial straits that the nation would never be able to pay its loan. In Paris, residents frequently succumbed to disease and lived in filth. As far as the army, revolutionary sentiment was rampant among lower enlisted soldiers who grew tired of their officers embezzling funds from the accounts meant to pay their wages.

An immediate impulse would be to blame Marie Antoinette for Louis’ blindness to all of this, and many historians over time have blamed her. She certainly wasn’t in any way likeable, nor could anyone seriously say she had no influence on the king whatsoever. But the republican case that was being made by the American founders, philosophers in Scotland, and writers in Louis’ own country like Diderot and Voltaire—that monarchy itself was an illegitimate concentration of power and wealth—had been gaining such rapid traction over the past 15 years, that to suggest discontent toward Louis’ rule was due solely to a promiscuous queen who liked to go shoe shopping reeks of an old world sexism. All without mentioning, of course, that the one man in charge of all the kingdom’s accounts, and tasked with distributing the funds therein, Claude Guillaume Lambert, was siphoning France’s money to enrich himself (he would, rightfully in my opinion, pay for this with his life in 1794).

All of this being what it is, we cannot pretend the French Revolution was without its own problems and evils.

First, the revolution was plagued by smaller sporadic counter-uprisings across the country, party and assembly dissolutions, endless constitutional scrappings and revisions, and lax enforcement of the barrage of laws passed by the new republic. Second, every revolution inevitably produces a fool who ruins it. This isn’t necessarily to say that revolutions can be so badly sabotaged that they are completely forgotten. Revolutions, once begun, normally remain relevant forever, though the ways in which they are relevant change over time. But insofar as the immediate victories and potential victories of a revolution, those tend to be squandered when a charismatic, righteous, purity-driven little snot eventually rises up and fouls things up. The Russian Revolution had Stalin, the American Revolution (I would argue) had Hamilton, and the French Revolution had Robespierre (conversely, every revolution seems to have a troubling tendency to end the lives or reputations of its best advocates, such as Trotsky, Paine, and Caritat). While I would argue that the first half of The Terror—beginning in January 1793—was right to execute the king, queen, and corrupt nobles, the second half of Robespierre’s Terror—beginning in June 1793—was nothing but a senseless descent into paranoia and bloodshed of ordinary people, including many Catholic nuns and priests who refused to go along with the revolution out of conscience. Third, the French Revolution was rife with antisemitism; this was the beginning of a recurring problem in French society, from the Dreyfus Affair to the Vichy regime to France’s current hostile climate toward Jews (an astonishing 55,000 French Jews have immigrated to Israel since 2009).²

What the revolution needed, then, was a person who could end its own chaos by: 1) replacing France’s web of complicated, obscure, hastily-passed laws with a clear, unified, easily-enforced legal code, 2) ensuring protection for all of its people (be they Jew or Catholic), and—most importantly—3) exporting democratic ideals to outside peasantry living under old, decrepit, authoritarian kingdoms that were taking too long to collapse. This person would be Napoleon. As the historian Andrew Roberts remarked during a lighthearted Intelligence Squared debate:

“What [Napoleon] did was to save the best bits of the revolution: equality before the law, religious toleration, the abolition of feudalism; and he swept away the worst parts: the ten-day calendar, the Cult of the Supreme Being, and The Terror’s mass-guillotinings. In a sense, one can understand why he felt it was necessary to do all of this, and why also the British, and indeed the Ancien Régime, the old reactionary powers, desperately wanted to get rid of him.”

Before moving on, I would like to take a moment to say that should you wish to learn more about France’s course of events leading up to Napoleon’s rise, there is no book I would recommend other than Eric Hazan’s A People’s History Of The French Revolution, though the perfect—and I do mean perfect—biography of Napoleon himself is Andrew Roberts’ Napoleon The Great. Do add these two volumes to your personal library, you won’t regret it.

On August 15th, 1769, Napoleon was born in the city of Ajaccio, on the small mediterranean island of Corsica to Carlo and Letizia Bonaparte. Much like the French king could not imagine a seat of power without him in it, the humble couple also couldn’t have imagined that it would be their children who would step in to fill the power vacuum. A family of minor nobility living on an island with no feudalism, the Bonapartes were not wealthy (although Napoleon’s great uncle did like to brag, tongue-in-cheek, that they “at least had enough land to never worry about buying wine, bread, or olive oil.”³) Letizia would go on to have 13 children; and of the eight who survived to adulthood, three would become kings, one a queen, and two would be sovereign princesses, along with the one who would be emperor of the nation that Corsica had recently attempted (and failed) to gain independence from.

Letizia is described as a well-educated, strong-willed, beautiful woman; one of the island’s most sought-after women, with porcelain skin, rosy cheeks, and long flowing brown hair. A devout Catholic, she was loving but strict toward her children. Carlo too was handsome and well-educated, but was also, by contrast, irresponsible with the family’s finances and mediocre as a diplomat and attorney. He quickly developed a so-so reputation as being kind but distant, sober yet frivolous.⁴ He and Letizia had married based on the prior arrangement of their parents, despite the fact that Carlo had been madly in love with another woman at the time of matrimony. There is some controversy, too, concerning whether Letizia, over the course of her marriage, secretly enjoyed the company of men on the side, such as the Corsican nationalist leader Pasquale Paoli or the Count of Marbeuf (to whom Carlo served as an assistant, and who later would help Napoleon gain entry into the exclusive Brienne military academy on the French mainland).⁵ Carlo and Letizia’s differences in personality were also exacerbated by their differences in religious philosophy. While Letizia was a Christian, Carlo considered himself a secular man. His reading preferences—and later his son’s—were the works of Locke, Hume, Montesquieu, and Hobbes.

The first decade of his life, Napoleon preferred books over playing with other children, and claimed that by the age of nine he had read Rousseau’s entire 800-page novel The New Heloise; a story which argued that one should follow one’s own heart and mind rather than social expectation, and a book the emperor later claimed had changed the course of his life. But in 1770, Napoleon’s secluded peace would come to an end when his father’s boss Marbeuf—the governor of Corsica, as well as a count—issued the edict that if Corsicans could prove noble heritage dating back 200 years, they would enjoy the same privileges as mainland nobility. Marbeuf then used this edict to assist Carlo in ensuring Napoleon was accepted, first briefly to Autun to improve his French and break him from his Corsican tongue, and then to Brienne.

Sent away, at last, to this military academy for youth 650 miles from anyone and anything he ever knew, the island boy had to learn to adapt to changes in climate, lifestyle, and class consciousness. In Roberts’ Napoleon The Great, we are given a glimpse not only of the education Napoleon received by others over the five years of his attendance, from 1779-1784, but are also given a glimpse of his autodidacticism:

“The monks [at Brienne] subscribed to the Great Man view of history, presenting the heroes of the ancient and modern worlds for the boys’ emulation. Napoleon borrowed many biographies and history books from the school library, devouring Plutarch’s tales of heroism, patriotism, and republican virtue. He also read Caesar, Cicero, Voltaire, Diderot, and the Abbé Raynal, as well as Erasmus, Eutropius, Livy, Phaedrus, Sallust, Virgil, and the first century BC Cornelius Nepos’ Lives Of The Great Captains, which included chapters on Themosticles, Lysander, Alcibiades, and Hannibal. One of his school nicknames—‘the Spartan’—might have been accorded him because of his pronounced admiration for that city-state rather than for any asceticism of character…. The intention [at Brienne] was to create a generation of young officers who believed implicitly in French greatness, but who were also determined to humiliate Britain, which was at war with France in America for most of Napoleon’s time at Brienne.”⁶

Upon leaving Brienne, Napoleon entered École Militaire in Paris, and once he graduated from there, became an artillery officer. When the drums of revolution began to rumble in the streets, the young officer readily accepted and promoted its Enlightenment principles, and in ten years, Napoleon took part in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and became ruler of France by popular vote. At last, in 1804, he was crowned emperor; a harken back to the Roman Empire, out of which emerged many of Napoleon’s influences as mentioned above: Caesar, Virgil, Hannibal, Cicero, etc.

Photographs I took in Paris: Colonne Vendôme (2019), Napoleon’s Tomb (2020)

The most successful lie told about Napoleon, first by monarchist propagandists intent on portraying him as a comical non-threat, and then unthinkably by cartoonists, hobby historians, casting directors, and middle school teachers up until the present day, was that he was short. A ridiculous little man with delusions of grandeur who wanted to play swords like a small boy. An upstart munchkin to laugh at and deride, but certainly not to fear (the propagandists would soon change their tune once the “little man” took Northern Italy). However, Napoleon was not short but of average height; in French units, he was 5’2”, which in modern international units equates to 5’7”. In sum, Napoleon never had Napoleon Complex.

Another taunt of English propaganda was that the French ruler was terrible with women. One favorite account, exaggerated and printed frequently by the royalist papers, was that when Napoleon was a young officer fresh out of École Militaire, he was repeatedly rejected by the prostitutes at the Palais-Royal in Paris’s red light district, despite proving he had more than enough money to pay for their services. No doubt the telling of this tale was intended to make Napoleon seem unattractive, strange, and so badly lacking in charisma that even his wages couldn’t do the work for him. It is not mentioned that Napoleon had just turned 18 when he went searching for a prostitute (it was only one occasion), that he was too shy to offer the prostitutes money directly (instead preferring to make small talk by asking them questions about their lives, which made them think he was a bother and not a customer), and—as soon as one of the prostitutes picked up on young Napoleon’s shyness—she put him at ease, took his money, and they had the expected interaction.⁷ This Napoleon of 1787 would be a far cry from the confident man of battle and intrigue that would be on full display at the turn of the 19th century. In fact, Napoleon would go on to have at least 22 mistresses throughout his life, seven of which he would write about, whilst others revealed who they were in their own writings or in conversations with acquaintances. I present this fact, not because a historical figure’s sexual history should be seen as a series of “conquests” for which they deserve some kind of weird credit, but simply as evidence that Napoleon was not—as the propagandists contended—a man the opposite sex found repulsive.

His devotion to Empress Josephine in the tumultuous early years of their marriage, however, certainly was not requited, and it was only a matter of weeks after their wedding in 1796—when Napoleon made his departure for Italy—that she took a French Army volunteer, Hippolyte Charles, as a lover. Upon finding this out two years later, while in Egypt, Napoleon himself would find consolation for his heartbreak in the first of his 22 mistresses: a novelist and painter named Pauline Flourés, whom he would refer to as “his Cleopatra”.* In a 2015 Evening Standard interview, the aforementioned historian Andrew Roberts reminds us though, that despite the infidelity and despite the emperor feeling more romantic affection toward the empress than she felt for him, Josephine and Napoleon still had plenty of desire for one another:

“‘[Their letters] are unbelievably erotic,’ says Roberts, ‘FULL ON.’ Like what? ‘Cunnilingus. Napoleon was obsessed by cunnilingus. Talked about it constantly. He’d tell her not to wash for three days because he’d enjoy going down on her when she was unwashed. It was really basic… Josephine did something in bed called zig-zags, and I’m desperate to find out what they are. I’ve done primary research, I’ve dug about, but couldn’t find anything. We also don’t know why Napoleon called her private parts the Baron de Kepen. Who on earth was the Baron de Kepen to have justified this sobriquet?’”⁸

(Dr. Pepper shoots from my nose and I cackle when Roberts—poor fellow—later mentions giddily in the interview that Harvey Weinstein has optioned his book for a “Napoleon & Josephine” television series. Aged like a fine wine.)

A New York Times article written by Caroline Weber on the bicentennial of Josephine’s death, sheds more light on the unsteady romantic and sexual dynamic between the emperor and empress, when she writes:

“For [Napoleon], these early days with ‘Josephine’—a diminutive variation on her middle name—were bliss. Six years younger than she and far greener in the bedroom, he was ‘baffled and excited by her repertoire of techniques’… In steamy billets-doux, the general praised his darling’s ‘little black forest’: ‘I kiss it a thousand times and wait impatiently for the moment I will be in it. To live within Josephine is to live in the Elysian fields.’ Josephine, for her part, tolerated his passion but didn’t exactly enjoy it. She even cheated on him while he was off conquering Italy in the summer of 1796. The balance of power between them shifted, however, as soon as Napoleon confronted her about the affair. From then on, Madame Bonaparte ‘was no longer the all-powerful, dishing out her favors from a pedestal’, and as her husband’s military and political fortunes continued to rise she grew increasingly fretful that he would leave her. With good reason. By the time he crowned himself emperor in 1804, Napoleon’s obsession with her ‘little black forest’ had yielded not only to countless extramarital amours but to an urgent desire for an heir, which Josephine never managed to provide. Although she lent elegance and grace to a court otherwise known ‘for its gold-splashed brashness’, the emperor decided he could do better, dissolving their marriage in 1809 so that he could wed the Austrian emperor’s 18-year-old daughter, Marie-Louise.”

Yet despite the scandal of a head of state divorcing his wife—not heard of since Henry VIII—Napoleon’s struggle to conquer love seemed to be a battle he could never win.

“The union with Marie-Louise fell apart when Europe’s other sovereigns, his new father-in-law among them, succeeded in crushing Napoleon’s empire. Forced to abdicate in April 1814, he staged a brief comeback in the following year, then lost again, definitely at Waterloo; an occurrence his ex-wife did not live to see. In May 1814, she expired after a bout of what was probably pneumonia. According to her maid, though, Josephine ‘died of grief’, heartbroken to have learned of her faithless lover’s fall. This news shattered Bonaparte in turn. Once in exile, ‘Napoleon never stopped thinking of her, surrounding himself with pictures of her at St. Helena (and eating off plates bearing her face).’ And when he died in March 1821, the last word he spoke was, apparently, ‘Josephine.’”⁹

But none of these (very late) responses to the propaganda of the monarchists is to say that had they looked a little deeper, or waited a little longer, they wouldn’t have found accurate ammunition to use against Napoleon. They certainly would have.

When it came to being a supporter of the cause of equality, he was a complete hypocrite during the Haitian slave revolt. Rather than embrace the uprising of free blacks against their colonial masters—and send a message to the monarchist world by making the tiny new nation an ally—Napoleon sent more than 60,000 French troops to the small island in an attempt to crush the rebellion. At this, the formerly-subjugated revolutionary leaders, Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, were dumbfounded.¹⁰

What’s more, General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas—father of the famed future novelist, and the highest ranking military officer in Europe ever who was of African descent—was treated horrendously by Napoleon after returning to France from captivity in Naples in 1801. Ill treatment that did not cease after his death in 1806, when the Dumas family had to beg the French government for a widow’s pension and backpay for Thomas’ time as a prisoner of war (to no avail).

A further wrinkle in Napoleon’s towering legacy was his decision to slaughter 3,000 prisoners of war during the siege of Jaffa in March 1799 - the ethics of which is still hotly debated today. On the one hand, the massacred prisoners had been prisoners of Napoleon before, and had previously signed a gentlemen’s agreement upon their release never to fight his army again; an agreement that—having now been broken—left Napoleon certain the prisoners would combat him a third time if released once more. “On the other hand,” others object, “Prisoners are still prisoners, regardless of how many times they are made so, and the act of killing unarmed men always carries with it a whiff of dishonor, no matter how justifiable the motive might be.” Decide for yourself.

What is incontestable, however, are the remarkable achievements Napoleon accomplished that subsequently led the western world away from absolute rule to representative governance for all people.

For the Jews of France at the dawn of the 19th century, the emperor came as welcome relief after centuries of persecution. “Throughout much of Europe in the 18th century, Jews had been forced to live in ghettos and even to wear yellow armbands. In 1797, while in Ancona, Italy, Napoleon was made aware of this fact and was absolutely amazed. He quickly ordered that the armbands be removed and that Jews be given the right to live wherever they wished. It was a policy that he would follow during all of his military campaigns throughout Europe,” says David Markham, president of the International Napoleonic Society.¹¹ And Napoleon would do more than this at great risk to his popularity and rule in France; convening a meeting in May 1806 between he and France’s rabbis, so they could inform him of the ways they still faced discrimination.

Napoleon is the reason Poland exists as a state; first being made aware of the cause for its independence from Prussia by his nationalist mistress Marie Walewska (who was a tireless advocate for Polish sovereignty and for the Polish people). He is the reason Paris, and the rest of France, saw improvement in the quality of its education and infrastructure; founding public schools across the country that standardized learning for all children, and having iron bridges constructed that connected the city’s two halves across the Siene. He is the reason French currency inflation went from 10,000% to just 6% in a year.

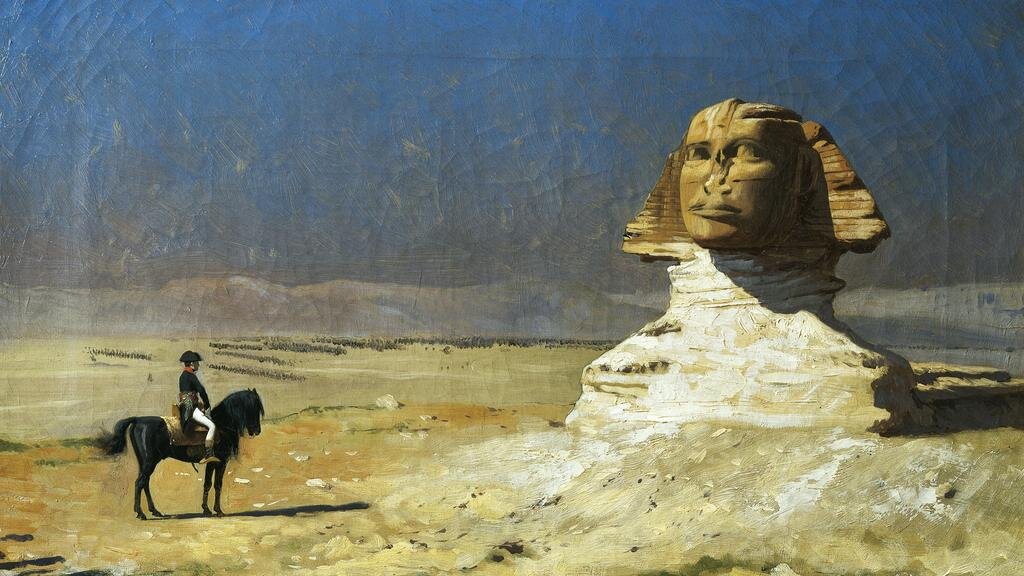

But by far the most intriguing example of Napoleon’s liberationist drive was his time in Egypt. With the English having a death grip on the Mediterranean, the British Empire allowed the Ottomans and Mamluk factions to essentially run the show in the land of the pharaohs, so long as their trade monopoly continued uninterrupted. The mission for the forces of republican France, then, was simple and twofold: 1) weaken the British hold on the Mediterranean by establishing French trade in Egypt, and 2) liberate the Egyptians not only from Turkish colonization, but also from Mamluk jihadists who sought to establish their caliphate in the country (much to the surprise of those who believe Islamic militance is a modern problem, or that Saudi Wahabbism is its origin point). Common punishments for religious infractions that were meted out to the Egyptian populace by the Mamluks were impalement, castration, and flaying of the skin.¹² In response to this barbarism, Napoleon would tell his soldiers just before landing, “The ideal of liberty that has made the republic the arbiter of Europe will also make it the arbiter of distant oceans and of faraway countries!”¹³

Yet when it came to liberating oppressed populations, Napoleon didn’t even wait till his boots hit the sand. On the way to Egypt he stopped at Malta for six days, and during that very short time he established a democratic governing council, freed political prisoners, abolished slavery and feudalism, and established a hospital, university, and postal service. What’s more, the voyage to Egypt was not solely a military one. Accompanying Napoleon were not only soldiers, but scientists, historians, artists, and linguists whom he had personally invited. Because of this, the field of Ancient Egyptology received a major boost, with accurate scale drawings emerging of the pyramids, cartouches, temples, and sphinxes, and more importantly—after 2,000 years beneath the earth—the Rosetta Stone was rediscovered and proved to be key for translating hieroglyphics.

Battling their way from the pyramids of Cairo to Acre (in modern Israel)** and then back to Cairo again—a brutal, brutal distance on horseback and on foot—Napoleon’s army succeeded in freeing the populations of Egypt and the “Holy Lands” from Turkish and Mamluk tyranny. However, the Egyptian campaign is generally described by historians as a failure because so many of Napoleon’s soldiers perished from the punishing sun. “Napoleon was economical with everything except the lives of his men,” scolds one Discovery Channel documentary, “The heat was unbearable and the soldiers began to strip off their uniforms as they marched… the dust parched their throats and the sand burned their feet.”¹⁴ But of course that was going to happen. It was hot. Everyone involved knew it was going to be hot. Egypt is hot. Presenting Egypt as a failure because his army had to march through the desert, wha- of course they had to march through the desert. Egypt is desert.

Still, the concession is unavoidable that the original purpose of establishing long-lasting French trade in Egypt—and thereby weakening British naval dominance of the Mediterranean—had indeed failed. In fact, Lord Horatio Nelson sank Napoleon’s ships off the coast only a month after the ruler arrived and marched inland. Upon receipt of this bit of news one bright morning as his staff were eating a celebratory feast in a palace, Napoleon turned to them and smiled: “It’s very lucky that you like this country, because now we have no fleet to take us back to Europe.”¹⁵ The French army would eventually find their way back home a year later, with Napoleon himself having to risk capture by British cruisers, and taking the roundabout path down Africa and onward to Sardinia. Along the way he would have come across the site of ancient Carthage; and one wonders if the sense of destiny he possessed ever since his boyhood—this dream of being the “Enlightenment Caesar”, in a way—was temporarily replaced by the feeling that, like Hannibal, he had been allowed to reach the pinnacle of glory in a land of mystery, only to be cast into outer darkness.

In the beginning of the article I said that Napoleon’s “invasions of kingdoms was the major catalyst that turned Europe democratic, and this was not unintended. He knew that the old monarchies had no intention of allowing their people to acquire self-governing powers.” And yet it should be clarified that though his goal was to export Enlightenment ideas, Napoleon was not actually a warmonger. Of the seven wars Napoleon’s army would fight in, from 1803 to 1815, Napoleon would initiate only two of them, and only as a preemptive measure against powers that would have attacked France’s republic if he had not (Spain and Portugal were chomping at the bit). It was not, then, that revolutionary France would not leave the rest of Europe alone militarily (as revisionists of the more Burkean conservative stripe insist), but that the monarchists of Europe—and primarily England—were hellbent on turning France into a Sodom and Gomorrah tale they could use if ever their own peasants got uppity.

Of all the monarchies who opposed Napoleon and revolutionary France, England was the most vociferous, because it stood the most to lose in terms of diplomatic influence and access to exotic natural resources if France ever inspired a revolt within England’s borders. It is also worth noting that with Napoleonic France’s declaration of freedom of religion, England being the only country where Protestantism was institutionalized in a sea of Catholic kingdoms suddenly became insignificant… which no doubt would have irritated members of the British aristocracy who saw their contrarian Protestantism as an intriguing and daring feature of their country. Having surpassed Spain as the dominant European power only 200 years before, England was not about to cede its imperial superiority—or perceived moral superiority—to France so soon; especially not when the rival country had a ruler belonging to a family from such minor nobility that they almost weren’t noble.

For Napoleon’s part, after his failure to secure Egypt as a French trading post in the Mediterranean, he made a second attempt to undermine British naval superiority by persuading allies to join what he called the “Continental Project”: a blockade which banned British ships and goods from entering French-controlled ports in Prussia, Russia, Denmark, Holland, and Spain (which was basically every port along the top of the continent). Intended to cause economic and political upheaval in England, the project backfired because the British Royal Navy simply parked their warships outside of all the ports they were banned from and prevented any French ships from docking, and traded with ease at ports of nations unfriendly to Napoleon like Portugal.

Had Napoleon managed to defeat England, not only by trade and on foreign battlefields, but by invading England itself somehow, the other monarchies—being weaker and financially reliant on the British Empire in many ways—would have capitulated. This would have meant that in the future there would have been no African colonialism, no Raj in India, no World War I, no World War II. However, such was not to be. As narrator Charles Nove describes in the 2019 documentary The Napoleonic Wars:

“Britain was master of the sea. Napoleon was unbeatable on land. Neither the whale nor the elephant were able to challenge the other in their own domain.”¹⁶

The emperor’s fortunes would not improve six years later in Russia, when—in an attempt to protect Poland from the aggression of Alexander I—Napoleon led his forces across the Nieman in June of 1812. Though Britain was unable to come to Russia’s aid because it had (foolishly) antagonized the United States into war that same month, Napoleon still had his work cut out for him when it came to the long march to Moscow. Nevertheless, he rode triumphantly through Russian-annexed Vilnius, where he was followed in the streets by old men and children who lit celebratory candles and sang in his honor. In a scene similar to when American GIs liberated Paris, local women from Vilnius rushed out to kiss the soldiers passing by, and in the evenings the French were entertained by choirs.

This initial luck would take a turn, however, at the Battle of Valutina-Gora, 244 miles from Moscow, when one of Napoleon’s main generals—Ètienne Gudin—bled out when a cannonball bounced from the ground and shattered the bones in his legs. In the aftermath of the battle, surgeons also ran out of supplies to treat the injured and had to dress wounds with their shirts, clumps of hay, and paper torn from books.¹⁷

The Battle of Borodino three weeks later was in no way an improvement. In fact, it was the bloodiest single day of war in all of human history up to that point, and wouldn’t be surpassed as such until World War I. “Overall,” Andrew Roberts notes in his biography of Napoleon, “the French fired 60,000 cannonballs and 1.4 million musket balls that day. Even if the Russians were firing at a lesser rate, and there is no indication that they were, an average of over three cannonballs and seventy-seven musket balls were therefore fired per second throughout the battle.”¹⁸

Though Napoleon had won at Borodino, it was a bitter victory. The emperor and his officers began to realize that Russia was too vast for a single campaign, winter was coming, 40,000 of 115,000 soldiers were either dead, wounded, or captured, and the army still had to cover 80 miles to take Moscow.

When Napoleon finally did reach Moscow, and walked into the city without a shot being fired, he was stunned to find that his conquest did not force the surrender of Alexander I. On the contrary:

Alexander was marching toward Moscow.

The vital organs, throats, and mouths of Napoleon’s high-ranking officers were being severely burned because the wine of the Kremlin had been replaced with acid.

And thousands of loyalists of the Russian regime, who had hidden themselves among Moscow’s populace, burned down 90% of the city when Napoleon was asleep (killing 12,000 of their fellow citizens in the process).

Despite every victory, Napoleon’s losses had become so great he had to admit defeat. The Russian monarchy had won its war, incredibly, without winning a single battle and losing its capital. To apply an American perspective, the losses suffered by the French in just 82 days equated to two Vietnams. Russia regained Poland at the Congress of Vienna in 1814, and Poland wouldn’t be revived as an independent state until 1918.

During the retreat from Moscow, when Napoleon’s army reached Vilnius once again—the city where, only three months before, they had been welcomed with cheers and open arms—20,000 French soldiers died upon arrival from starvation, hypothermia, and typhus. Reverential old men, lovestruck women, and singing children now oddly absent, the townsfolk threw these casualties in unmarked mass graves that wouldn’t be discovered until 2001.

At the same time Russia regained Poland in 1814, Napoleon would face his final war in France itself. The English, Spanish, Austrian, and Portuguese empires had combined forces to invade the country with the goal of reestablishing a monarchy; a monarchy that had no popularity among the people who had overthrown the last one nearly 25 years before. Faced with odds that were steep to say the least (a million enemy versus 200,000 of their own), cowardly officials in the republic schemed behind Napoleon’s back to collaborate with the occupiers. In fact, in an effort to weaken the emperor’s morale, Napoleon’s own brother Joseph attempted—but failed—to bed Marie-Louise, while Napoleon’s brother-in-law, King Murat of Naples, struck a deal with the Austrian army to keep his kingdom if he did not fight on behalf of France (a decision that would not save him from an Austrian firing squad two years later). But Napoleon’s Foreign Minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand—a rat face whose lack of principle earned him the nickname “shit in silk stockings” by his peers—was arguably the worst of the cowards: scurrying to his desk to pen a letter to the enemy generals, informing them that the siege defenses of Paris had been neglected and that they should march on the capital as soon as possible.¹⁹

Napoleon, unaware of this treachery, continued to battle bravely and victoriously in the French countryside; at one point having his horse explode beneath him from a howitzer shell while he himself remained unhurt! Yet for all the courage and fortune in the world, there were simply too many invaders and not enough French to sustain the string of victories. An inverse joke of fate, when one thinks back on Russia: that though Alexander won whilst losing every battle, Napoleon lost whilst winning every one of his.

On March 30th, Paris fell. Louis XVIII (brother of the headless one) was placed on the restored throne by foreign powers against the will of the common people, while Napoleon was exiled to the island of Elba six miles off the coast of Tuscany under British guard. The Emperor of Austria, Francis I, who, in addition to being Napoleon’s enemy in the takeover of France in 1814, also found himself in the weird position of being the father of his second wife, ensured that Marie-Louise returned to Vienna instead of going to Elba. On the way there, she became the lover of Count Adam von Neipperg… the enemy general Napoleon’s brother-in-law in Naples had negotiated with to keep his crown. Scoundrel brother Joseph, meanwhile, stole jewels and fled to the United States (Mexicans, for whatever reason, mocked him by sending a satirical offer to crown him Emperor of Mexico, and when he took the offer as serious and accepted, he was of course subjected to more mockery). Though Charles Talleyrand escaped the justice he deserved for ushering foreign powers into Paris, for the rest of his life he would be followed in public by harassers shouting “There’s the man who betrayed France!” until eventually he became reclusive. When he sought to make amends with the Catholic Church on his deathbed in 1838, several priests refused to attend his bedside before one finally—reluctantly—agreed to anoint him and say last rites.

The reign of Louis XVIII was greeted like a wet blanket. French soldiers refused to salute officers who had not been part of Napoleon’s legions, and on Napoleon’s birthday, celebratory cannon fire echoed against Paris’s brick walls along with shouts in the streets of “Long live the emperor!” in direct contradiction to Louis’ orders. His wife, Marie Joséphine of Savoy, had died four years prior of edema, and the rumor in the palace among the courtiers spread that the marriage had been unconsummated for years because of how repulsed she was by his obesity - a cruel irony. She wouldn’t have been wrong however. Louis waddled more than walked back-and-forth from his throne to his chambers, and even employed a muscular servant to push him toward the table in his chair when he sat down to eat. Moreover, with Austrian, English, Portuguese, and Spanish forces still occupying France, he had no actual power. This above all, his citizens resented the most. The revolution had given them freedom and Napoleon had given them glory. In return, the unified monarchist powers of Europe gave them a crowned pig and robbed them of their sovereignty. Further fanning this flame, official documents marked the reign of Louis XVIII as being in its nineteenth year… as if the revolution had never happened.

Meanwhile, on Elba, by 1815, Napoleon had been demoralized for some time on receipt of the news that Marie-Louise was no longer true to him. But when he got word that the army was still loyal to him, what came next was reinvigoration. Outsmarting British patrollers, he escaped the island on a ship he had been allowed to own (to supply himself with goods from the Italian mainland), and landed back on French soil two days later. To the king and his foreign installers, a “risen” Napoleon traveling from town-to-town—gathering a peasant army as he went—must have seemed like the Pied Piper refusing to accept his damnation without taking others with him. But to the revolutionary Frenchmen who had spent the past year being humiliated and demoralized, this was akin to the Second Coming, as the conqueror strode on horseback through their village streets like Jesus in Jerusalem. One account from the outskirts of Laffrey, in the rural southeast of France, tells of Napoleon riding with a small guard between two hills when a battalion marched on him from both sides. Unbuttoning his jacket and pointing to his heart, he shouted “Will you fire on me?! Will you?! Will you shoot your champion?!” Instead, they dropped their muskets and ran to lift him up on their shoulders.²⁰

All in all, over the course of three months, after landing back in France essentially alone, Napoleon managed to amass over 300,000 soldiers and encountered no resistance from Cannes to Grenoble to Lyons, continuing northwards until—on the afternoon of March 20th—he and his forces approached Paris. Ten hours before this, King Louis, in a panic, had fled in a carriage he had to be lifted and placed into by his entourage (the width of the carriage doors had been customized to fit his size), and at first he sought refuge at a military outpost in Lille, where the garrison promptly declared their loyalty to Napoleon and chased him away. But eventually the king found friendly faces… in Belgium.

As if Napoleon being lovingly mobbed by soldiers at Laffrey were not enough, Col. Léon-Michel Routier (who served under Napoleon in Italy, Calabria, and Catalonia) recounts in his diary the scene he witnessed upon the emperor reentering Paris:

“The carriages enter, we all rush around them and we see Napoleon get out. Then everyone’s delirious. We jump on him in disorder, we surround him, we squeeze him, we almost suffocate him... The memory of this unique moment in the history of the world still makes my heart pound with pleasure. Happy, like me, was the witness of this magical arrival, the result of a road of over two hundred leagues travelled in eighteen days on French soil without spilling one drop of blood.”²¹

You have no idea how much I wish this were the end of the story. Really. If I could tie a bow on the life of Napoleon right here—accurately—the world would have been a better place for it.

But the monarchs of Europe, who had only just withdrawn from France, simply were not going to allow Napoleon’s retaking of it to continue without a fight. While the Russians and Austrians needed time to prepare their armies once again, British and Prussian forces in Belgium were already gathering half a million soldiers for the invasion. In his nonfiction bicentennial tribute to the war, Waterloo: The History Of Four Days, Three Armies, & Three Battles, renowned historical novelist Bernard Cornwell summarizes the emperor’s thinking on the coming danger as such:

“Napoleon calculated that if he could beat those two armies, then the other allies would lose heart […] He could have waited to raise and train more men until the French army almost matched the allies in number, but those two armies north of the border were too tempting. If they could be divided then they could be beaten, and if they could be beaten, then the enemy coalition might collapse.”²²

Napoleon’s hope was that by beating the British and Prussian armies before the arrival of the Russians and Austrians, then the Russians and Austrians would not continue to prepare for war against him; thereby securing his reign—and the French Republic—for life. His opportunity came on the 18th of June, 1815, when he preempted invasion by the coalition, and met both the Duke of Wellington and Prussian Field Marshal Gebhard von Blucher on a battlefield just northeast of Braine-l’Alleud, at Waterloo, across the Belgian border.

Initially, the battle looked as if it would go Napoleon’s way. The Duke of Wellington had failed to commit his reserves at Hougoumont Farm on the emperor’s left flank, a cavalry back-and-forth led to heavy losses for the Union Brigade, and a British Army Major General—William Ponsonby—was lanced to death by French soldiers before they trampled his body with their horses.

But when one of Napoleon’s generals, Michel Ney, looked out into the distance and thought he saw the British infantry retreating, it would prove to be a fatal mistake. Leading his cavalry to charge, only to find that the enemy infantry had in fact not retreated, but had organized into small circular formations with fixed bayonets, Ney and his men were forced to ride around impotently and many were shot from their saddles. Moreover, at Hougoumont, half of the attacking French force had managed to break through the gate only to have the doors shut behind them. Once trapped inside, they were all slaughtered.

The Duke of Wellington would later claim that this division of Napoleon’s left wing was the moment that decided the outcome of Waterloo; but most historians agree that the decisive blow to the French Army was when Blucher’s Prussian forces arrived and attempted to outflank the French from the rear. To keep this from happening, Napoleon had to send his reserves to intercept them at a small village called Plancenoit, where brutal fighting kept those reserves bogged down for the rest of the battle. Taking advantage of the vulnerability, the Duke of Wellington commanded his soldiers to advance, and as a result the Imperial Guard—Napoleon’s most elite and feared unit—were massacred. At that, Napoleon had been defeated for the final time.

The casualties were so plentiful at Waterloo, that due to an extreme lack of medical care, many of the battle’s wounded were left over several days to die right where they had fallen. Local scavengers made small fortunes pulling teeth from the mouths of the corpses that littered the field; selling them to dentists who bought the grim trophies by the thousands to use them in the manufacture of false teeth. In fact, for a generation after the battle, dentures throughout Western Europe were known as “Waterloo Teeth”.²³

As for Napoleon, he had no choice but to surrender himself to foreign monarchs once again. But fearing that his execution would inspire insurgent warfare conducted by devoted revolutionaries in France and in their own countries, it was agreed that Napoleon would be sent into exile a second time far far far from the continent, on the island of St. Helena, whose nearest coast was southwest Africa 1200 miles away.

There he would spend the last six years of his life softening his demeanor; befriending a little girl and her dog, and entertaining them both with a sword made of rolled-up paper and (very watered-down) tales of his adventures. Betsy Balcombe, the 12-year-old daughter of two East India Company administrators, would hear all about the exploits of the aging Frenchman in the funny hat who, at one time in his life, tasted the wine of Tuscany, gazed at the wonders of the Egyptian pyramids, and trekked through miles of Russian snow, whilst having little—if any—awareness of the impact these journeys had on the families of soldiers who marched beneath his banner. Knowing him only as a kind “uncle” who had appeared, at random, in the middle of her isolated life, Betsy (and her dog) would be at Napoleon’s bedside when he passed away in 1821.

The victory of the European monarchs, even without the threat of a returning emperor, would be short-lived. Nine years after Napoleon’s death, the July Revolution of 1830 ended “Divine Right” on French soil once and for all. Louis XVIII had died six years before from a combination of obesity, gout, and gangrene, and was replaced by his younger brother Charles X. During the six years of Charles’ rule, the death penalty was imposed on anyone who mocked Catholicism and financial indemnities were made to be paid by the poor to the nobles who had lost their property in the revolution. Unconcerned—even defiant—about the egalitarian feelings of his people, his days as king were clearly numbered. When the July Revolution broke out in the streets of Paris, Charles X fled to England and never returned. With Russia weathering riots due to food scarcity and plague outbreaks, Austria recovering from a series of nationalist revolts, the Kingdom of Prussia dealing with a religious schism between Lutherans and Old Lutherans, Spain bogged down in Central and South American conflicts, and Britain experiencing the death of their king and the election of liberal Whigs, none of the European powers were willing (or able) to take on France again.

In the beginning I stated that Napoleon’s “invasions of kingdoms was the major catalyst that turned Europe democratic”. This is because even though the continent’s kings and nobility ultimately were the ones who ensured Napoleon’s demise, his legacy as a general and emperor would inspire nations to move away from the monarchies that had ruled them for centuries, and toward democratic and parliamentary systems that still continue to this day.

I also stated in the beginning that to read about Napoleon was to read about an almost messianic figure. Yet his story does not end quite like the stories of other messiahs. Simon of Peraea rose up against the Romans in Israel, only to be cornered by centurions in a maze of cliffs and speared to death on the orders of Valerius Gratus. William Wallace fought the English for the independence of Scotland, only to be publicly disemboweled, quartered, and have his head displayed on a stick at London Bridge. Rasputin—a less noble savior—would ascend from a Siberian village to a royal palace only to be poisoned, stabbed, shot, strangled, and frozen, before the entire Czarist system came tumbling down, and the family who had placed so much trust in him was also murdered. In a way Napoleon was lucky… or unlucky, depending on how you look at it. While spared the typical gruesome demise of the revolutionary deliverer—a good thing for him as an individual—he was also denied a kind of glory that comes with martyrdom. Allowed to grow old and fat, he faded into an irrelevance that threatened to diminish his image. This perhaps leaves you, as it leaves me, with an unkind thought: Napoleon died at Saint Helena, but should he have died at Waterloo?

Footnotes & Citations

*After Egypt, Pauline kept up her interesting life. Along with continuing to be a painter and novelist, she also became rich in the Brazilian timber trade, developed a fondness for smoking a pipe and wearing men’s clothes, and adopted dozens of pet monkeys and parrots before returning to Paris with them and living to the age of 90. When her estranged husband expressed dismay at her affair with Napoleon, she revealed that she not only had slept with the emperor during her time in Egypt, but with two of his friends as well, and then divorced him.

**Napoleon’s fiercest enemy in Jaffa and Acre (both located in modern Israel) was a ruler named Ahmed Jezzar, who—in addition to getting sadistic pleasure from beheading the messengers of his rivals, shodding the feet of his captured enemies with horseshoes, and having seven of his wives executed—also possessed an impressive knack for crafting origami flowers that he would later gift to his foreign visitors.

1. “History vs. Napoleon Bonaparte”, Alex Gendler, Ted-Ed, February 4th 2016; 2. “Antisemitism In France: A Prejudice That Hardened In 1789 & Which Has Come In Waves Ever Since”, The Independent, Andreas Whittam Smith, January 14th 2015; 3. Napoleon The Great, “Corsica”, Pg. 4, Andrew Roberts, 2014, Penguin; 4. Ibid., Pg. 6; 5. Ibid., Pg. 10; 6. Ibid., Pg. 12; 7. “Napoleon the Great? A Debate With Andrew Roberts, Adam Zamoyski, & Jeremy Paxman”, Intelligence Squared, November 24th 2014; 8. “Historian Obsessed With Napoleon Spills The Beans On Bonaparte’s Sex Life & Reveals The Truth About ‘Not Tonight, Josephine’”, Evening Standard, Charlotte Edwardes, June 10th 2015; 9. “Review: ‘Ambition & Desire: The Dangerous Life Of Josephine Bonaparte’ By Kate Williams”, New York Times, Caroline Weber, December 5th 2014; 10. “The Black Jacobins: A Review Of C.L.R. James’ Classic Account Of Haiti’s Slave Revolt”, International Socialist Review, Issue #63, Ashley Smith, January 2009; 11. “Napoleon Scholar Details Emancipation Of European Jews”, Arts & Culture, STL Jewish Light, Robert A. Cohn, December 15th 2010; 12. Napoleon The Great, “Egypt” pgs. 180-181, “Acre” pgs. 188-189, Andrew Roberts, 2014, Penguin; 13. Napoleon The Great, “Egypt”, Pg. 166, Andrew Roberts, 2014, Penguin; 14. “Napoleon’s Obsession: The Quest For Egypt”, Discovery Channel, 2000; 15. Napoleon The Great, “Egypt”, Pgs. 177-178, Andrew Roberts, 2014, Penguin; 16. “Napoleonic Wars: Parts 1-6”, Epic History TV, October 9th 2019; 17. Napoleon The Great, “Trapped”, Pg. 597, Andrew Roberts, 2014, Penguin; 18. Ibid. 604; 19. Napoleon The Great, “Defiance”, Pg. 705, Andrew Roberts, 2014, Penguin; 20. Ibid., “Elba”, Pg. 735; 21. Ibid., “Elba”, Pg. 738; 22. Waterloo: The History Of Four Days, Three Armies, & Three Battles, Chapter 1, Pg. 26, Bernard Cornwell, 2015, Harper Collins; 23. “The Dentures Made From The Teeth Of Dead Soldiers At Waterloo”, Paul Kerley, BBC News Magazine, June 16th 2015