“You must be ready to burn yourself in your own flame. How else could you rise anew if you have not first become ashes?”

—Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra—

✦✦✦

It’s been two-and-a-half years since I’ve written on this website. Two-and-a-half years since I deleted Facebook, canceled Netflix and HBO, and whittled the number of friends I regularly talked to down to four. Decluttering life by moving away from technology and unproductive activities, as well as knowing which relationships to prioritize and which to let go, has worked wonders for my inner peace.

Prior to making these choices, there was a feeling of being overwhelmed by multiple writing projects that I wanted to do well and not mediocre:

When it came to reviews of books or films, there was a weird pressure (self-imposed) to always be reading or watching something.

When it came to op-eds, keeping up with world events involved not only maintaining contact with a fair number of journalists, activists, and other writers, but also involved a lot of travel to different places (which involved having to save a lot of money).

When it came to my essays on history, the amount of labor that went into research took up so much time and money that producing them without some form of monetization no longer made sense (on one occasion, I spent $100 on a rare book to get a single citation for an article that only generated 300 clicks the first six months and no donations).

I was tired. But more than just tired, it became apparent that if writing was going to be anything more than a hobby, I would need time to develop better strategies for revenue.

So in December 2020, I took a break.

My eight thousand regular readers gradually (then rapidly) left to find more active authors. Editors of different magazines detected my lack of enthusiasm for their pitches, and the regular exchange of emails once filled with suggestions, rejections, and banter dried up. Within three to four months, digital tumbleweeds were blowing across inboxes that were once full. And for the time being, that was exactly what I wanted.

What since has transpired over the course of 30 months has, surprisingly, been more travel; I’ve dived deeper into a love of cigars since having my first one in 2017; my reading has become more regular—averaging one book a month—with classical literature being prioritized over other genres (more about which classic literature in Whiplash II); I paused my career as a defense contractor; and I finished a southern crime novel.

But what is likely the most noticeable difference about my life now, in contrast to what it was two-and-a-half years ago, is that I’ve gotten married. My wife is a wonderful woman with a sharp mind and generous heart, who looks like a supermodel and makes the best damn tacos in the universe. She likes my love letters and I like watching her dance; she does not like my dark and dirty humor, and I don’t like her decorative pillows and very specific instructions for laundry. All of which is to say that we make each other happy in ways men and women should make each other happy, and drive each other crazy in all the ways men and women should drive each other crazy.

At the risk of coming across overly sentimental, there are certain songs that pair with certain seasons of life, and in the past few months the lyrics to “Ordinary World” have struck me as a perfect match for mine:

What has happened to it all?

Crazy, some’d say

Where is the life that I recognize?

Gone awayBut I won’t cry for yesterday

There’s an ordinary world

Somehow I have to find

And as I try to make my way

To the ordinary world

I will learn to survive

Yet though these developments certainly impacted the trajectory of my life for the better, they are not entirely or even mostly the reasons for how I have changed, or, for that matter, why I have chosen to resume writing after such a short amount of time (originally I had planned a break of at least five years).

A big part of what’s changed about me in the time I’ve been away is that I believe in God again.

Which couldn’t have happened at a more inconvenient time.

In February 2020, just before the pandemic, I had published a book called Embrace The Void Bravely (& Other Secular Sermons), which made the case for living an optimistic life without belief in God. Specifically it was a book that offered a cheerful nihilist approach to love, purpose, friendship, happiness, and death. It received a lot of praise and was blogged about and posted across platforms like Instagram and Facebook by fans who lauded its “hope” and “affirmation”. Looking back, I can’t help but wonder if they continued feeling that way about the book’s advice during the outbreak of Covid and the worldwide lockdowns… because its author folded like a cheap lawn chair in a light breeze. But why?

You notice the quote at the top of the essay from Nietzsche. There are two kinds of people who read Nietzsche: 1) readers who take his “death of God” as a grim warning about the emptiness of modernity and what lengths humans will go to fill the void of meaning, and 2) readers who see Nietzsche’s “death of God” as an invitation to a neverending party where we, over time, can “create meaning” along with futuristic paradises. In my case, I was the latter Nietzsche reader who became the former. Until very recently in life, I bought into the entire “basket” of naive modern presuppositions: the inherent goodness of human beings, the trajectory of history inevitably going in the direction of progress (rather than history being cyclical with periods of advancement and decline, and “progress” being a somewhat subjective term), the fundamental desire of all persons being liberty and not safety, and that all of that was quite independent of a “fairy tale epistemology” and able to be derived from pure reason. As the slogan of the American Humanist Association went, we were “Good Without God”.

Then 30 happened. When I turned 30, we were a year into the pandemic, and everything I thought true about the irreligious modern world over those past 12 months had been completely upended.

“Human beings naturally long for liberty.” Nope.

“Human beings will rebel when treated like cattle in need of herding.” Nope.

“Western governments will surely recognize that people have needs beyond mere sustenance, and consequently will end lockdowns as quickly as possible.” Once again, a big fat NOPE.

(“Human beings are inherently good?” Hahahaha.)

I was astonished—and maybe for the first time in life, genuinely repulsed—by not only the public’s willingness to comply with extreme pandemic restrictions, but eagerness to comply and shame others into complying. Stories of nosy self-deputized assholes shouting at people for jogging, cycling, and going to the park during lockdowns. An account of a neighbor peeking over the fence and telling a woman, “That’s the second time you’ve been out in your yard today.” A news report of a man spitting on hikers who dared to walk the trails without wearing their masks. Or my personal favorite: this finger-wagging article written by a weak, lispy, clown university administrator panicking that college students might be enjoying Thanksgiving at the same table as their families instead of eating “responsibly” in separate rooms (as you peruse this guy’s prissy op-ed, rend your clothes and cover yourself with ashes over the fact we’re no longer a nation that enjoys John Wayne).

But all these examples of paranoia on the part of individual losers pale in comparison to what governments got away with during this time. Australia using facial recognition software to “bust” people defying lockdowns, and sending people to detention camps if they were infected (and the New York Times justifying it). Scotland denying IVF treatments to women who refused to be vaccinated. New Jersey using drones to disperse outside gatherings. If the excessive pandemic restrictions achieved one good thing, it was that they demonstrated to me that the idea that Enlightenment secularism was somehow the “guarantor of rights” was a joke I had taken far too seriously far too long.

Thus began a reconsideration of everything I once cherished about political secularism, the supremacy of science over other forms of knowledge, and the entire Enlightenment project. It became immediately (and uncomfortably) apparent to me that without a transcendent order to appeal to for what was just and unjust, our liberties could easily be discarded (not just by world leaders but by ourselves) in order to embrace a technocratic elitist dystopia comprised of “experts” and serfs. But worse, a dystopia not restricted to any one place; a dystopia truly inescapable because it would cover the whole world.

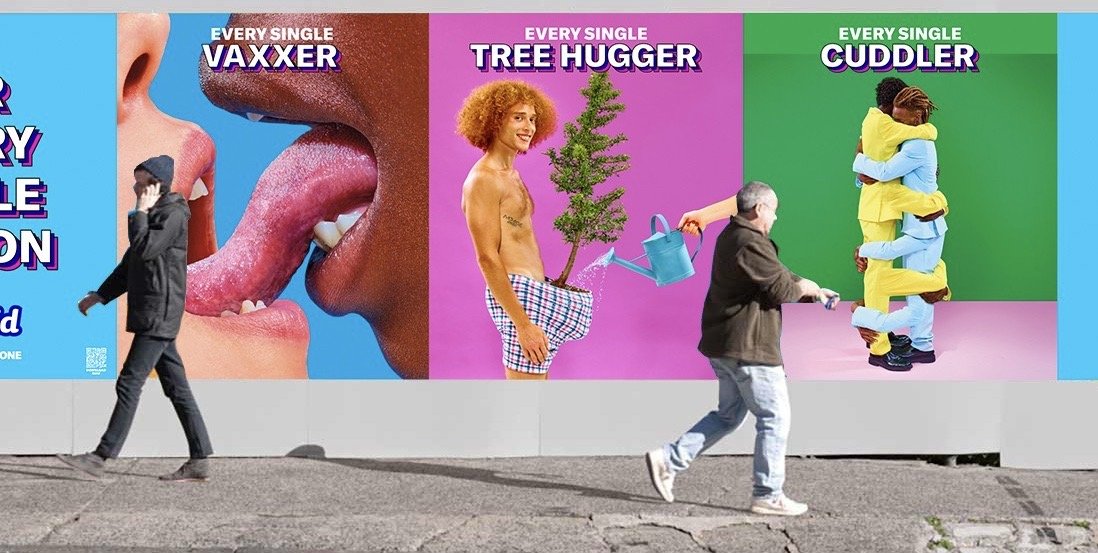

A seasoned believer will quickly note that God emerging from the embers of my charred heathen imagination was—at least initially—rooted less in curiosity and enchantment, and more in despair. That my Damascus moment came about as a frightened response to liberal scientism’s authoritarian streak; to mention nothing of my simultaneous growing hatred of the public spaces of Western countries, immersed as they were in distraction, fear, uniformity, and vulgar advertising, while empty sloganeering masqueraded as “wisdom” on signs, stickers, and clothing.

Ever the history enthusiast, I couldn’t help but notice that Antiquity and the so-called “Dark Ages” thereafter produced some of the most magnificent mythology, poetry, places of worship, and personal and family legacies filled with grand purpose (good and evil, granted, but grand nonetheless). Meanwhile our “so much better” time produced hopelessness (as relativism is incapable of setting goals to hope for), atomized individuals, hyper-specialization, and ugly brutalist architecture built around concepts like “sustainability” and “efficiency” but not beauty and certainly not meaning.

But when my “newly-minted redpilled” rage somewhat subsided, flirtation with a return to theism didn’t remain at despair. Curiosity and enchantment did follow.

From early-2021 to early-2022, a metaphysical boredom paired with a worldview crisis prompted me to seek out a one-time encounter with psychedelics. When you’ve been an atheist for eight years, and you’ve had the mindset for so long that says there is no reality beyond the physical, it’s almost impossible to “jolt” yourself out of that rut without a little extra help. Or at least for me that was the case. And for so many, I think, the transition process from belief to cold rationalism functions as an irreversible “lobotomy of imagination” which filters the sublime, the fantastic, the miraculous into black-and-gray matter. But in the spring of last year, a very mild dose of psilocybin was able to clear the neural pathway of a man who couldn’t entertain the existence of a supernatural realm—even when I really wanted to—and allowed me to open my heart to the possibility of a coexistent spiritual world and its Sovereign Ruler. Forgiveness for all the terrible things I’d done? What a beautiful aspiration! A life after death? What hope! What joy!

Of course, I am not unaware that to abandon “dignified reason” for faith over a drug trip sounds ridiculous, and in the minds of most skeptics, returning from materialism to spirituality under any circumstance is a bit like putting wet swimtrunks back on after drying off. You just don’t do it. Unbelief is supposed to be a one-way ticket. And also yes, I know, I really know, you really don’t need to tell me: I get that neither drugs nor pandemics nor a “kids these days” diatribe is proof of God.

But it’s not my goal to give you proof, however one might define that, although this isn’t because I don’t have any arguments. On the contrary there have been plenty of arguments for the existence of God I have found persuasive. It’s just that I’m wary of presenting a return to faith as a mere ascent of the intellect, when in truth it’s actually a much grander transformation in how one emotionally beholds the world, the cosmos, and every creature therein. Thus, instead of offering here a list of reasons for God’s existence, I’d rather be more intimate and share a prayer I’ve been praying everyday multiple times a day for the past several months:

“Lord, I believe in you. Help me in my unbelief.”

On the surface this seems a very strange kind of prayer, but if thought about for more than five seconds, it’s anything but strange. Because it’s not as if a rediscovery or re-acceptance of a transcendent reality is somehow a magic switch that, once flipped, undoes in an instant all the habits of an unbelieving mind. The reversal of unbelief by belief is at once a fast and slow-moving process. Sure, you believe in a God, and that’s a big step, but do you really think He’s the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob? Do you really think He had a Son who died for your sins and then rose from the dead? This takes a lot of time. And more than a lot of time, it takes a certain type of praying for a higher power to chisel away the residual doubt that stubbornly remains (or even is subconscious).

And it’s for this reason, I suppose, why I’m being somewhat chickenshit—or maybe not quite “chickenshit”, but noticeably evasive—about giving a complete account on how I arrived at God: because the purpose of this essay is to quickly update readers upon my return about why my future writing will be different from past writing. It’s not, however, the right format for a full-on conversion account. For that, a book is needed, and a book is exactly what I’m working on right now titled The Epiphanies.

The Epiphanies will actually be two books in one volume describing in detail my religious and political shift (the first, about religion, being called Riddles From Empty Space, and the second, about politics, being called Cravats Roasting On A Burning Tire), set to be released either in 2024 or 2025. At the moment all I can say about the project is that the cover is going to look very elegant, I’ve hired a magnificent illustrator, and the partial manuscript I’ve sent out has collected some really kind endorsements by some great people.

I realize I’ve just given a warp speed update on a pretty significant life change—not only to theism, which itself is a tectonic shift in worldview—but to belief specifically in the Judeo-Christian God. But again, keep in mind this is an update, not an account. Be on the lookout for The Epiphanies either in 2024 or 2025.

And now Part II of my return, which goes into much more detail about how the past few years have changed me politically.